The lay of the land

California is an exceptionally large and diverse piece of real estate. It starts at the coast. For 400 miles from Crescent City down to Santa Barbara the coast ranges stand as a barrier between the cold water of the Pacific Ocean, flowing down from Alaska, and the inland valleys of the state. The range is generally comprised of two ridge lines, an outer, which lies along the coast and an inner which marks the western edge of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys. The outer ridge has a coastal ecosystem with Redwood and Douglas firs comprising its forests. The inner ridges are generally much dryer and are comprised of chaparral and lots of Oak trees.

California is an exceptionally large and diverse piece of real estate. It starts at the coast. For 400 miles from Crescent City down to Santa Barbara the coast ranges stand as a barrier between the cold water of the Pacific Ocean, flowing down from Alaska, and the inland valleys of the state. The range is generally comprised of two ridge lines, an outer, which lies along the coast and an inner which marks the western edge of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys. The outer ridge has a coastal ecosystem with Redwood and Douglas firs comprising its forests. The inner ridges are generally much dryer and are comprised of chaparral and lots of Oak trees.

California is a very diverse state geography wise. The coastal ranges have a very large effect on the rest of the state’s climate.

Between these two ridges generally lies a series of valleys. Highway 101 mostly runs up these valleys, occasionally kissing the coast on the seaside of the outer range at Santa Maria, San Luis Obispo, and Eureka. Mainly, its route takes it through those valleys, through cities such as Paso Robles, and Santa Rosa, and one major urban center, San Jose, and Silicon Valley. San Francisco itself, which 101 traverses through is actually on top of the outer ridge, albeit a part that has dropped in altitude.

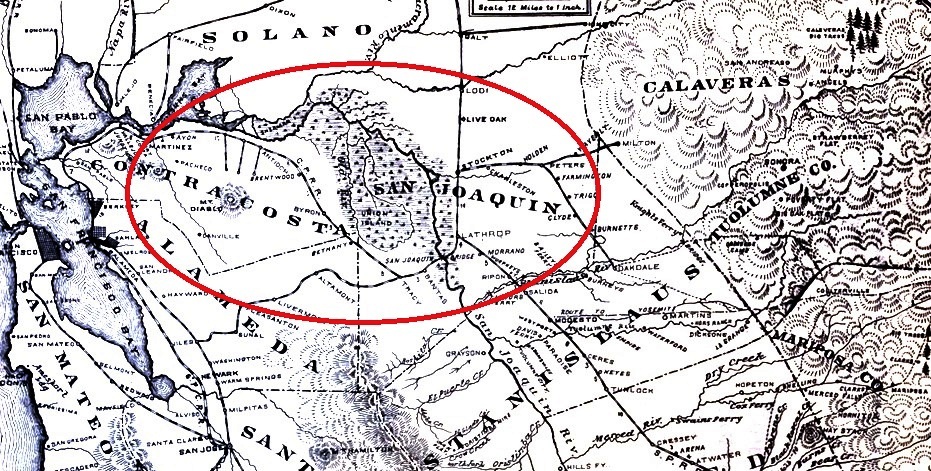

Inland to the east lies an exceptionally large valley, known as the Central Valley. The northern half is called the Sacramento and the southern half the San Joaquin. Together they are 40 to 60 miles wide and run 450 miles north to south, covering 18,000 square miles and comprising 11% of California’s total area. More than half of the state’s vegetables, nuts, and fruits come out of this area. It is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world.

Up until about 600,000 years ago the valley was thought to be an inland sea, called Lake Corcoran. It is believed to have formed when its outlet, near present day Santa Barbara closed as the Pacific plate side of the San Andreas fault continued it slow march northward. Some believe that the Monterey Canyon, in Monterey Bay, which rivals the Grand Canyon in geographical dimensions, was the result of erosion from the outflow of that drainage.

Eventually the lake breached the coastal range near the San Francisco bay and the resultant scouring by the water flow created the Carquinez Strait, which today is the path that the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers use to empty into the bay.

Lake Corcoran

What would have been most of the eastern shore of Lake Corcoran is the Sierra Nevada. Our story takes place in the foothills of the Sierra. Sierra is Spanish for range of mountains. Nevada means snowy. It is 400 miles from its northern end where its butts against the Cascade Range, to its southern end where it merges with the Transverse Range, which buttresses the Los Angeles basin against the western reaches of the Mojave Desert. The width of the Sierras is 70 miles across. The height of its peaks increases from north to south, with the tallest peak being Mt. Whitney, over 14,000 feet in height, it is east of Fresno. From there the elevations rapidly falls off as you go further south. The western slope is gradual compared to its eastern end, which is a steep escarpment. The eastern slope forms what appears to be a wall as you approach from the east. This is because of how the range was formed.

The mountains owe their existence in part to a rift zone called the Walker Lane. It runs from the Salton Sea in the southern part of the state, through western Nevada, and up into Oregon. It is believed that this break in the North American plate takes 20-25% of the total movement of the Pacific Plate northward. This action along with the much more famous San Andreas rift, caused the uplift four million years ago. Erosion has exposed the granite that comprises the range. This uplifting continues. While the 480 million-year-old Appalachian Mountains, which were equal in height to the Rocky's at one time, now have no peaks above 6300 feet, erode away, the Sierras are slowly getting taller. The Sierras have about 500 distinct peaks over 12,000 feet. Because of this they collect most of the snow and rainfall headed east.

This is why Nevada is a desert for the most part. For the last few million years it has been in a rain shadow because of the Sierras. Most storms come off the Pacific to the west and move east over the coastal ranges, the central valley, and then the towering Sierras. For the storm clouds to clear the Sierras, they need to rise, which causes the vapor they are carrying to condense and drop their moisture as rain or snow to clear the range. As they press on past the Sierras, they have little moisture left to drop on places to the east.

The Carson Range, a ridge of mountains between Lake Tahoe and Carson City, is considered a spur of the Sierras, and it also extracts a fair amount of precipitation. As the second set of ridges behind the Sierras it gets snow later and loses it sooner than the main Sierra ridge on the west side of the lake, and it receives only about half the snow that the main ridge east of the lake gets.

Looking to the west from Reno is the same pass that most settlers took into California. The mountains are part of the Carson Range. It is also the path that the infamous Donner Party took late in the fall to disastrous results.

From the Carson Range looking northeast back towards Reno and the Great Basin.

West bound the elevation changes quickly leaving Nevada. Then over the next 80 miles it slopes much more gently to the Sacramento Valley floor.

Lake Tahoe

Looking from the southeast corner of Lake Tahoe. The Sierra is on the left, and the Carson Range is on the right.None of the water from this large Alpine Lake ever makes it to the sea. It flows east out of the Sierras, through Reno and eventually disappears into the desert that is the Great Basin. About 80 miles east it disappears into a couple large sinks, and what is left into Pyramid Lake where it evaporates.

The original inhabitants

Humans have been in the Coastal Ranges and the Sierras for 10,000 years having migrated out of Asia over the Beringia land bridge between present day Russia and Alaska and spread out across North and South America. About 8,000 years ago the last ice age ended, causing sea levels to rise. This flooded the land bridge, and at the same time the sea level rose enough to turn a broad valley that faced the sea through a gap in the coastal range, now known as the Golden Gate, into a large bay, which includes the San Francisco and San Pablo bays. In geological time the bay filled in quite rapidly with the water level rising an inch per year until it was essentially its present size around 5000 BC, the sea level having risen 300 feet.The humans, the original Americans, naturally settled into groups or tribes. In the bay area that tribe was known as the Ohlones. They resided south of the golden gate, along the peninsula, through what is now Silicon Valley, and the Santa Clara valley, as far south as Monterey. Their lands adjoined the Miwoks. The coastal Miwoks resided north of the Golden Gate.

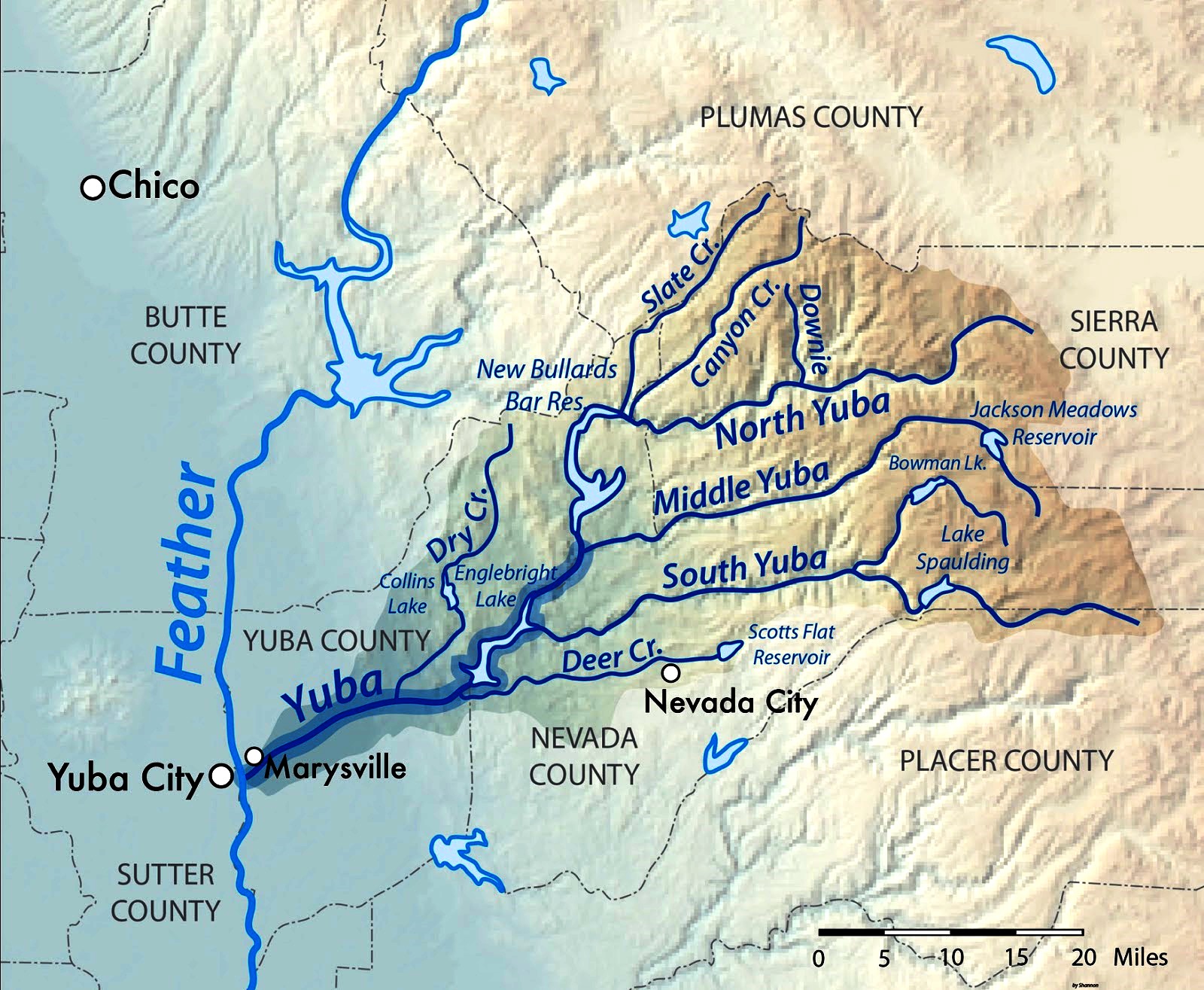

There were other groups of the tribe that inhabited the delta, the Sacramento area, and up into the Sierras southwest of Sacramento. To the north were the Nisenan who lived in the Yuba River and American River watersheds. This includes present day Grass Valley. They are a part of the larger group that was known as the Maidu. This whole combined territory extended west and north of the Nisenan. The Nisenan have also been known as the Southern and Valley Maidu. Some believe that the Maidu might have descended from the Martis, a tribe that first appeared in the Sierras 4000 years ago, as artifacts from them have been found in Auburn, a town 25 miles to the south of Grass Valley.

Maidu territory

Nevada City is adjacent to Grass Valley

Over the last 5000 years the Native Americans had seasonal use of the upper elevations, with movement to the lower elevations below the snow line in the fall and winter. Small mobile groups likely crossed the Sierra Nevada foothills between about 5000 and 10,000 years ago. Within the last 2000 years, the Maidu tribe showed up as a distinct culture.

The Maidu and Washoe tribes reportedly shared the head waters of the Yuba and the Bear River drainage above the snow line for hunting. The Washoe was a tribe from the Great Basin, with a western range to the crest of the Sierras and the Lake Tahoe area. It was also reported that occasionally hunting parties would attack each other.

The Europeans Arrive

Replica of Cabrillo's ship

First Spaniard to sail up the California coast.

In 1530 a group of Spaniards led by Herman Cortez reached Baja California. In 1542 Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo sailed into the San Diego Bay. Before the year was out he had reached as far north as Monterey. This was only 50 years after Columbus landed in the Bahamas, and then Cuba. Columbus mistook these islands for Asia and Japan. When Cabrillo set out for Alta or upper California, he found that the coastal winds and currents off the coast of California, with few safe harbors found, stalled the Spanish colonization of Upper California. The Spanish did not get serious about asserting control over the northern territory for another 200 years.

Early Spaniard sailors found that California's central and north coast can be treacherous.

What might be considered the first actual world war was the Seven-year war which started in 1756. In America it is more generally known as the French and Indian War. It squared off Great Britain, Prussia, and Portugal, against France, Spain, Austria, Russia, and Sweden. It started in the American colonies when the British attacked the French over disputed territories. The conflict quickly escalated to warfare at sea, and then jumped into Europe.

The seven-year war showed Spain that its hold on its North American empire was tenuous. Spain lost its holdings in Florida. It did gain the Louisiana territory from France, but ceded it back to France in 1800, who turned around and sold it to the U.S. in 1803. This prompted Spain to concentrate on its territories in the western part of North America. Spain proceeded to construct 21 missions and four strategically placed military forts or presidios at San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterey, and San Francisco.

The presidios were used to garrison soldiers and their families to both conquer and colonize the area. The missions hosted the Franciscans to minister to local converts. Around these facilities small towns or pueblos sprang up.

In 1804 Alta California was made a separate province of New Spain, which was the name of all the territory that Spain held in North and South America. A few years later events back home in Spain sowed the seeds of major changes on the horizon in the new world. Napoleon Bonaparte forced Spain's king to abdicate, replacing him with Napoleon's brother. This caused many overseas territories of Spain to set up juntas to rule in the name of the deposed monarch. This touched off a fervor for full blown independence by many American-born Spaniards. This culminated in Mexican Independence in 1821. This was not France's only injection into Mexican politics. In the 1860s an invading French force was able to overthrow the current Mexican government and install a monarchy that was an ally of it. The French viewed this move as a restraint against the growing power of the U.S. With an ongoing internal insurgency in Mexico and with support from the U.S. after the end of its Civil War, France decided that the war was un-winnable and withdrew.

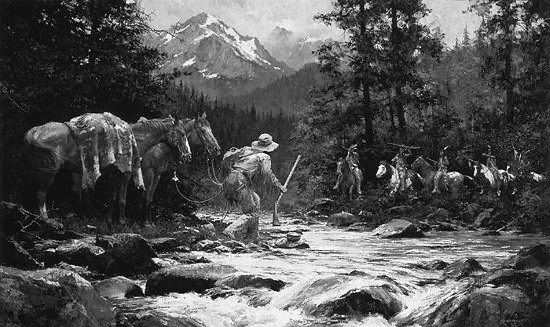

Trappers and hunters made their way west in the early 1800s, and along with the Lewis and Clark expedition to the northwest, people from the east started venturing closer to the west coast. By the 1820s the far west was becoming more known to Americans in the east. In 1842 and 43 John Fremont led his first two of five expeditions out into the western frontier, the first two to Oregon. Instead of heading straight back after the second trip he headed south to explore the Great Basin. Turning west at present day Minden, Nevada with his party they attempted a route over the Sierras, that the local Washoe Indians advised against in the winter.

They almost became a precursor to the Donner party when they had to resort to eating dogs and horses to survive the trek. Kit Carson, a member of his party, helped guide them over the Sierras through the pass which Fremont named in his honor, Carson Pass. From the summit of the pass, Fremont was one of the first Americans to see Lake Tahoe about 30 miles to the north. They continued down the south fork of the American river until they reached Sutter's Fort for supplies. Fremont made three more trips to explore the west, a couple in search of rail routes to the west.

Monterey Presidio

The Seven year war, in which Spain lost territory in the east, prompted Spain to concentrate on its territories in the western part of North America. Spain proceeded to construct 21 missions and four strategically placed military forts or Presidios.

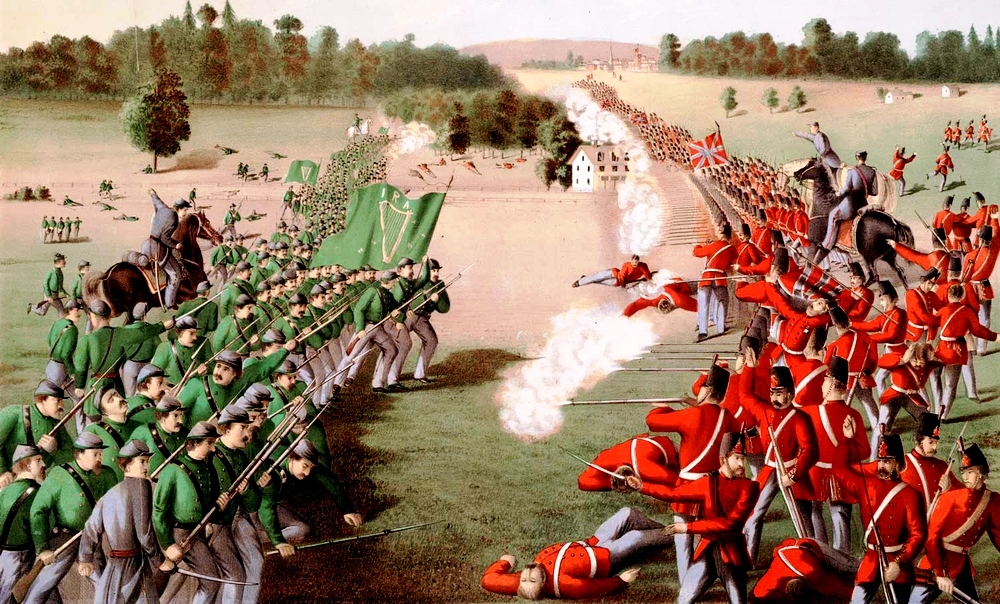

The Battle of Puebla in 1862

The Mexicans defeat of the French

in this battle is what Cinco de Mayo

originally Commemorated.

The French interfered

twice in Mexico's sovereignty.

By the early 1840s pioneers were starting to venture west in increasing numbers. The first popular route was the Oregon Trail. The trail was first used about 1811 by fur traders and trappers. In 1836 the first organized migrant wagon trail took off from Independence Missouri for the Willamette Valley in Oregon. The trip took almost half a year.

Oregon Trail

First major highway to the west. While its well-traveled path made it knowable and predictable, it also made it dangerous as the constant use of its prime camping and grazing spots spread disease.Like many routes it followed river valleys as grass and water were necessities for people and their animals, namely oxen, mules, and horses. The path through Nebraska and into Wyoming saw hundreds of thousands of Buffalo until 1870. They were a source of food, and the chips a source of fuel for cooking. What could not be eaten fresh was often turned into jerky for later in the trip. By the time the buffalo were disappearing over 400,000 emigrants had traveled the route.

One of the many perils facing our travelers were that the groups tended to camp along the same spots, as those were the ones with ample water and feed for the animals. Due to cholera epidemics between 1849 and 1855 the water in these spots became contaminated with the disease as one of the effects of the disease is acute diarrhea, the result of which is often the contamination of the local water supply due to the primitive sewage disposal on the trail. Thousands died on these trails before they ever got to the Rockies.

California Independence

The genesis of California becoming independent of Mexico began in Texas. The Texas Revolution in 1836 was prompted by an ever-increasing American immigrant population in the area. After some initial routs by the Mexicans over the rag-tag Texan Army, the Texans became better trained and equipped. In the Battle of San Jacinto, the Texans this time routed the Mexicans, and forced them back to south of the Rio Grande. They also captured Mexico's President and General Santa Anna. Texas ended up sending Santa Anna to Washington, D.C. which sent him home.In the meantime, unrest was brewing in Mexico and Santa Anna was deposed. Texas declared its independence, which Mexico refused to recognize. Skirmishes continued into the 1840s while turmoil within the new republic simmered until Sam Houston was elected the first President and a resolution requesting annexation by the U.S. was drafted. During this time Mexico was also distracted by the first French intervention in 1838, It was mainly a blockade of some Mexican ports over claims by French Nationals over losses due to the unrest in Mexico.

When the U.S. annexed Texas the stage was set for war between the two countries. Mexico still considered Texas Mexican territory. The U.S. preemptively declared war on Mexico.

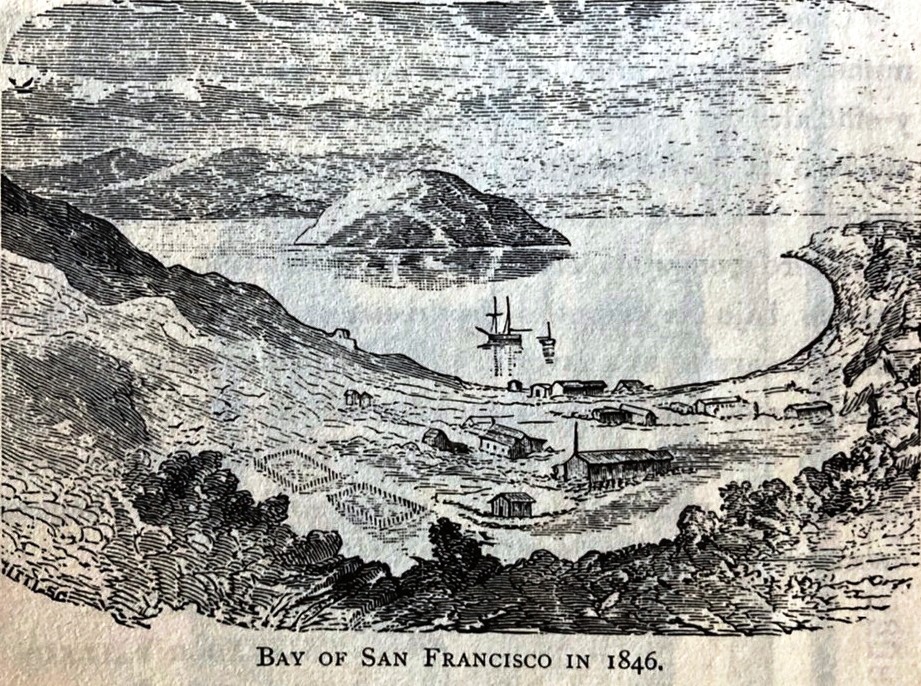

Although declared in May of 1846, word did not get to the American Consul in Monterey until early August. At that time about 10,000 Californios (Hispanics) lived in California, primary on cattle ranches near present day Los Angeles. That population comprised about 800 families. There were about 1,300 Americans, scattered in the northern part of the state from Monterey to Sacramento, with more pouring in every summer from the trails discussed, and more making the perilous sea journey around Cape Horn, or the equally treacherous dual boat trip, with a slog across the Panama peninsula. Most were landing in San Francisco. There was also about 500 Europeans in that northern area. There was also a small population of Russians centered around Fort Ross, about 60 miles north of San Francisco. But their peak population came around 1841 and was declining. It only ever consisted of less than 100. During this time, the Native American population was probably around 50,000, down from over 300,000 in 1770. People of European extraction, including Californios, where still a distinct minority.

Sailors landing in Monterey

Some of the 3000 sailors and marines aboard 10 U.S. Navy ships in the area were put ashore to secure the seized ports

With the start of the conflict Mexico issued a proclamation that unnaturalized foreigners could no longer have land in California and were subject to expulsion. This prompted rumors in the Sacramento Valley among American settlers that General Jose Castro, the senior Mexican military officer in California was preparing to move against them. As a preemptive measure those settlers, many from Sutter's Fort (Sacramento), seized an undefended Mexican outpost in Sonoma. This was the start of the Bear Flag Revolt, as that flag was raised over the post. By July, 300 occupied the fort. Besides the volunteer militia, it was joined by lieutenant colonel John Fremont and his contingent of 60 cartographers, scouts, and hunters. These actions were authorized by the Commodore of the U.S. Navy Pacific Squadron, Robert Stockton.

Sailors landing

Although at the start of the conflict the U.S. Navy had no official west coast ports, it sent over one half of its force to the area at this time. It was supplied by store-ships which purchased supplies and water from local ports and the Hawaiian Islands. On July 2nd, the Navy and Marines captured Alta California's capital, Monterrey. They then started taking other California ports, landing in Yerba Buena, soon to be renamed San Francisco, on July 9th.

Since the U.S. Army, with the exception of Fremont and his small company, had no troops in California, Stockton decided to lessen the crew size on the three frigates, four sloops, and three store ships, about 3000 sailors and marines and put some of them ashore to secure the seized ports.

At the same time the California Battalion was formed, headed by Fremont with a Marine Lieutenant promoted to Major, second in command. Fremont requested that the volunteers elect their officers. Most of the elected were immigrants of the California trail the year before or members of Fremont’s expedition. Battalion members were authorized pay of $25/mo. Excellent for the time. There was 34 Mission Indians that joined, and they were paid with trade goods, which was common at the time.

The Battalion's first mission was to sail its 160 members south to assist with the capture of the pueblos and Mexican settlements in Los Angeles and San Diego. There were several skirmishes in Los Angeles where the Americans would capture and then be forced to retreat under attack from Californios, both there and in Santa Barbara. The Americans also landed a 360-man force at San Pedro that was also repulsed. The Americans withdrew.

In late November 100 U.S. Calvary arrived from the east after a grueling march across the Sonoran Desert east of San Diego where they promptly lost 21 in a short battle against 100 Mexican calvary. The American Force was under siege for four days until a 215-man American force came to their aid. In December the California Battalion, now 428 strong arrived in San Luis Obispo, and two weeks later took back Santa Barbara.

Other reinforcements came also. The Mormon Battalion was the only religious unit in the U.S. military. They served a year from July 1846 to 1847. The U.S. needed their help in fighting the war with Mexico in California. Brigham Young, a spiritual founder of the Mormons, urged his followers to form a battalion, of roughly 500 men, and march to California in support of the United States. There were three benefits to the Mormons; a chance to demonstrate their loyalty to the country, and for the group to bring income into the church, and to go to a place, besides the planned but yet to happen exodus to Salt Lake, where they wouldn't be a distinct minority.

The Mormons followed the Santa Fe trail into the southern reaches of California. They joined up with other forces from the east and another regiment that had also arrived from the east, but by ship. They helped occupy southern California after the hostilities ended.

On January 8, 1847, a re-enforced 600 strong American force from the east met in battle with an ill-equipped 500-man Californio force about 10 miles southeast of present-day downtown Los Angeles. That same day Fremont's force arrived in San Fernando Valley. The next day the eastern force now commanded by Stockton fought a 300-strong force of Californio militia, which had some artillery, which they positioned just south of Los Angeles. Stockton aimed all his available fire on the Californio's canons, which forced their artillery to have to retreat. After a counterattack by Californio calvary was driven back, most of the Californios deserted, allowing the Americans to march into Los Angeles.

This ended armed conflict over the American conquest of California. A treaty was signed between Fremont and Mexican General Andres Pico on January 13, 1847. The wider war finally came to a complete end in February 1848 after the U.S. captured Mexico City in September of the year before. Mexico ceded California, Texas, and much of the territory in between. Because of the disagreements over whether conquered Mexican land would be slave states or not, many thought that the Mexican war helped lead eventually to the American Civil War.

For the next three years California was run by military governors. Local governments were generally run by alcaldes or mayors. In 1849 the last military governor called for a constitutional convention, which was held in Monterrey. Its 48 delegates, who were mostly pre-1846 settlers, and eight native born Californians unanimously outlawed slavery and set up a government that ran eight months before it was given statehood September 9th, 1850.

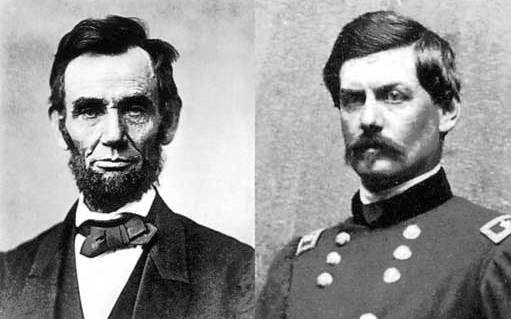

While Fremont helped to popularize the west with his timely scientific reports, co-authored by his wife, he was considered a war hero, and also a traitor during the interlude when the U.S. military took over California from Mexico, as he refused to step down as temporary military governor. While not found guilty of mutiny he did receive a dishonorable discharge from the Army, and while President Polk re-instated him into service, he did not pardon him. Fremont was considered impetuous and controversial, and his life was often contradictory. Right after his problems in California he was one of the state's first Senators. He was the first Republican presidential nominee in 1856. Lincoln, the second Republican presidential nominee relieved him of duty for insubordination during the civil war. At times he was wealthy due to land ownership during the gold rush, but he died destitute, not in the west, but on the east coast in New York City.

California statehood was part of the Compromise of 1850. California was admitted as a free state and Texas as a slave state. It was a complex set of legislation that in the end made no one happy. In some respects, it attempted to rain in slavery, and in other respects, it enforced the concept of humans owning other humans. At best it postponed the Civil War for ten years.

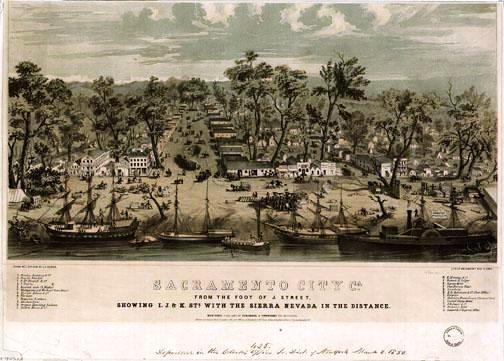

Sacramento

The 400-mile-long Sacramento River is the largest river in California. Before the railroads, water navigation often determined where settlements appeared. The cities namesake river is why Sacramento is where it is. We will also see how Sacramento helped make towns like Grass Valley feasible. Today the Sacramento metropolitan area has well over 2 million people, and Grass Valley, along with Nevada City are considered well within it spear of influence.

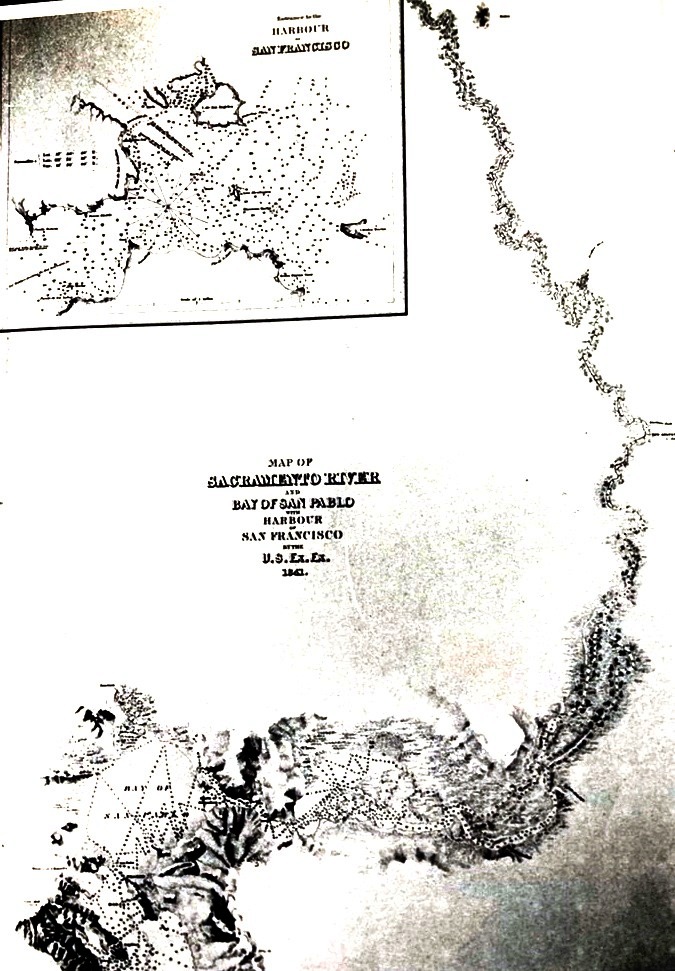

The San Francisco bay: lower left

Sacramento: Upper right

Before there was a settlement known as Sacramento the Nisenan group of the Miwoks inhabited the area. The tribe did not engage in agriculture, and were hunter-gathers, mainly foraging for nuts, berries, and fishing the local rivers. The original Spanish and English explorers did not see much value in the area, as did Gabriel Moraga, the first European to travel through the area in 1808. Moraga gave the river its original name which was later anglicized and shortened to Sacramento.

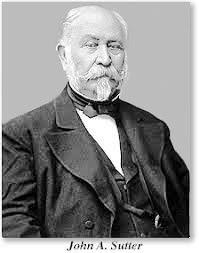

Except for a few trappers, hunters and the occasional explorer, the area stayed European and American free. That is until John Sutter found his way to California in 1839. He was a German-born Swiss immigrant of American citizenship. He dreamed of starting a New Helvetia (Latin for Switzerland) in his new home. He appealed to the Mexican Governor of then Alta California, Juan Bautista Alvarado to let him start a settlement in the territory. The governor liked Sutter's plan of a settlement in the Central Valley, as he saw it a buttress in the frontier to manage the natives, and also encroaching Americans, British, and Russians with no cost in troops or treasure.

Alvarado's condition for giving the grant was that Sutter had to reside in the territory and become a Mexican Citizen, requirements he met in 1840. He was granted 44,000 acres and commenced building "Sutter's Fort," at the edge of a marsh the was then part of the Sacramento river, that year. Sutter put together an army consisting of Native Americans and named himself a general. He ruled over New Helvetia with absolute power. As his army grew and he bragged about his power the Mexican government started to grow weary.

In 1841 Sutter got thrown in jail briefly for backing an unpopular governor who had followed Alvarado, after Alvarado took back the governorship in a coup d'état. But not before the deposed governor tripled the size of his grant. That year Sutter established the first large scale agricultural settlement in Northern California, just south of present-day Yuba City on highway 99, about 40 miles north of Sacramento. He had orchards and vineyards planted, grew grain, and raised cattle. He planned to retire there.

In 1845 a Mexican official offered to buy his land, which he declined and said he later regretted.

During the 1846 Bear Flag revolt the Americans captured Mexican General Mariano. The rebels demanded that he and other Mexican captives be housed in Sutter's prison. Sutter reluctantly agreed to raise the Bear Flag over his fort, but he treated the prisoners, especially Vallejo, who he considered a friend, as guests and not prisoners.

Sutter tried to keep a sense of normalcy during the conflict, but the hostilities resulted in a shortage of manpower to work his varied businesses.

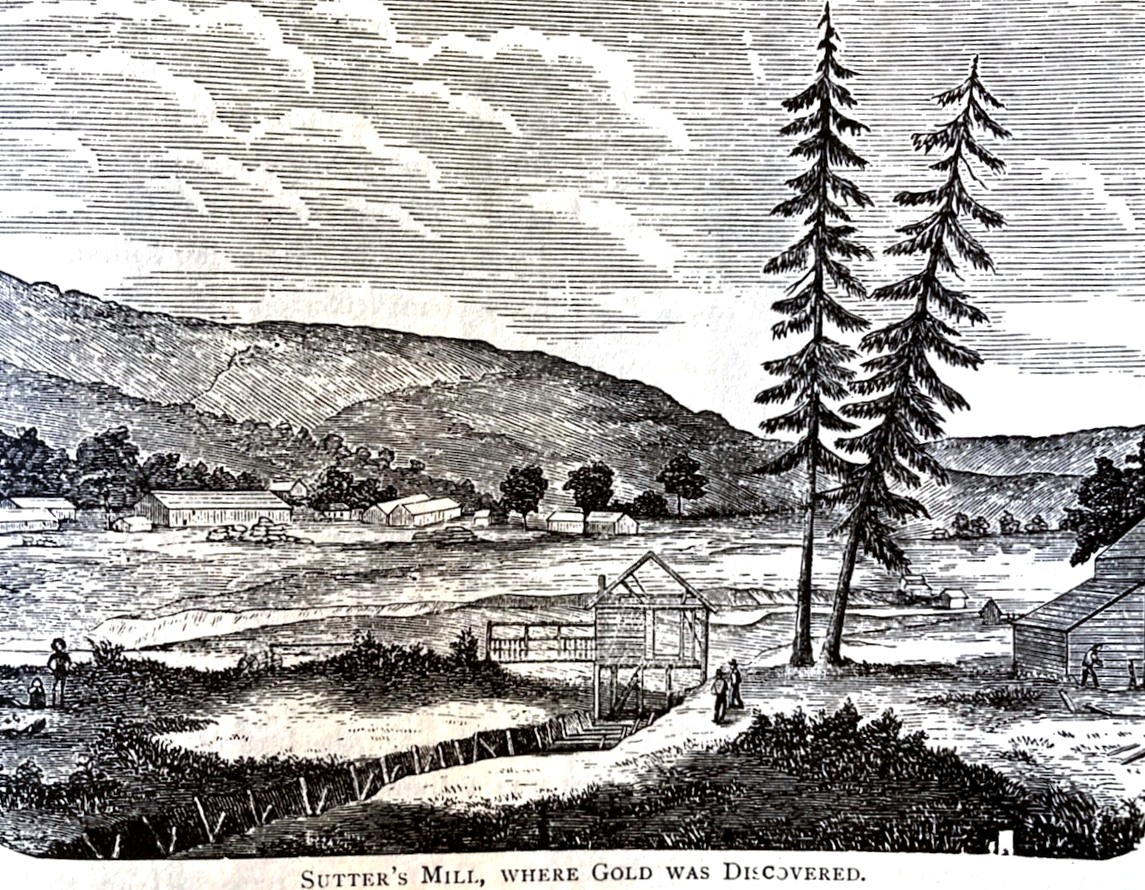

In 1847 Sutter sent associate James Marshall up into the foothills along the South Fork of the American river to construct a sawmill as Sutter wanted the wood to start to build out a town around the fort. In January of 1848 Marshall discovered flakes of gold at the mill. Word leaked out almost immediately when a newspaper publisher in San Francisco visited the mill and found gold himself. Those the closest to the area, including many from San Francisco, flooded northeastward towards New Helvetia. They overran his holdings and slaughtered herds of his livestock, drove out natives that were loyal to Sutter, and simply decimated his integrated businesses tied to his land. The new intruders simply divided up his land into claims without his consent. He decided to retire to his farm and left his son in charge of New Helvetia. Sutter's Fort was soon abandoned and left to decay.

American River: Sacramento and Sutter's Fort on the left

Columa discovery site upper right

Both sites today

By the end of the Civil War in 1865, Sutter could no longer maintain his estate as the manpower needed had been pulled into mining, and that led to a decline in farming income. Squatters were looting timber off his land and rustling cattle. Both him and his son aggravated their financial situation by becoming entangled in some bad business deals and swindled out of some property. This left Sutter broke. On June 21, 1865, a vagrant ex-soldier, who Sutter let hang around, but had been whipped for stealing, set Sutter's mansion on fire. Lost was all of Sutter's personal and historical papers. He lost priceless art and other relics. Sutter also found himself in U.S. Courts trying to defend the property deeded to him by the Mexican government. He ultimately lost the farm and left California five months later to petition Congress for redress. He died in a Pennsylvania hotel in 1880 never seeing the justice he was after.

The towns real start was on the Embarcadero or wharf that John Sutter and Samuel Brannon built at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers, right before Sutter retired. This new port was becoming a debarkation point for those seeking gold.

Originally Sutter had John Bidwell and Lansford Hastings, layout a town in what is now the southern part of Sacramento on a bluff overlooking the Sacramento river near present-day Land Park and zoo in 1844. It was just a few miles south of the current downtown area. Each of the two would receive a share of the lots. But when Sacramento started growing around the embarcadero to the north the town fell into decline. While what became the center of Sacramento was at water level, this original area was not and did not make for a good port.

Bidwell was one of the leaders of the first wagon train to come down the Humboldt River in Nevada, which became the California trail. They deviated at the Humboldt Sink and headed southwest over the Sierra and arrived in California near present day Modesto. Bidwell was only 22. But Sutter hired him shortly after his arrival in the Sacramento area as his business manager. Bidwell later discovered gold on the Feather River at what became known as Bidwell's Bar, underwater now as part of Lake Oroville. He also obtained the rank of Major while fighting in the Mexican American war, and later became a Congressman from the state.

Hastings was a different story. He was the one that advocated the use of what came to be known as the "Hasting's cutoff," an ill-advised "shortcut" out of Wyoming and into Utah to get to California. It was the Donner party's use of the so-called cutoff that got them into trouble on Donner pass, as the shortcut was not a shortcut, and it made them arrive late in the season to attempt a Sierra crossing. Hasting's endeavors did not end with his advertised cutoff. He was educated as a lawyer. After visiting Alta California in 1843 and seeing how sparsely populated it was, when he returned east in 1844, he decided to help wrest California away from Mexico and make it an independent republic. Because of that he wrote a pamphlet called "The Emigrants Guide to California" to get Americans to move there and overrun it much like was done in Texas. He was infamous for promoting his "Hasting's Cutoff" shortcut, a route he never completely tested himself, which got the Donner's in so much trouble.

Hastings served as a Captain in the California Battalion in the Mexican war and was a delegate in the 1849 California Constitutional Convention before moving his family to Arizona in the 1850s where he served as a postmaster and a territorial judge. During the Civil War Hastings sided with the Confederates, and saw an opportunity to again wrest California away, this time from the U.S., and finally become an independent entity. He even promoted the idea to Jefferson Davis, the Confederate's President, who liked the idea and promoted Hastings to the rank of Major in the confederate army and ordered him to assemble a military unit in Arizona. The war ended before anything would come of it.

After the war, Hastings, like many disgruntled ex-confederate soldiers left the U.S. for Brazil. He wrote "The Emigrants Guide to Brazil." He died in 1870 conducting a shipload of settlers to a colony he had set up there.

The town that Sutter had tried to set up was naturally named Sutterville, and while one of the first brick structures in the west were built there in 1847, the settlement that was growing up around the embarcadero at the mouth of the American River soon surpassed Sutterville, and now only some street and place names mark its presence. Eventually Sacramento grew and encompassed the area.

Much of Sutter's empire, and the agricultural utopia he was working towards was built on the backs of others, often at great cost. While Sutter had some Miwoks, who worked voluntarily for him, the manpower Sutter had been using to build his empire was to a large extent by hundreds of natives who were forced to work in near slavery. It is claimed that they were housed, and fed like cattle, including a complete lack of sanitation.

Even after California became a state in the union, a declared free one at that, the official legislative stance was that natives had little or no rights, at times even the right to exist was on the table. With the discovery of gold many of the natives were able to scatter, but their futures were not all that bright over the long term.

The town of Sacramento, while becoming an inland port had its share of setbacks. Flooding was always a problem, and the potential lives to this day. As early as 1850 the first recorded flood occurred. The Sacramento River during the winter can be swollen from its own water flow from the far north, along with often an equal or greater flow being dumped into it by the Feather River, which is not too far north from the present-day metropolitan airport. Add to that three branches of the American River that converge 25 miles east of the Sacramento River in present day Lake Folsom into one torrent, and disaster is set.

Map from the 1870s show the large marsh areas where the San Jacquin and Sacramento rivers met. Now that area is a large group of islands surrounded by levies, mostly used for farming, with many sloughs and river channels runing throughout. Sacramento is just off the top of the map.

The first railroad section between Sacramento and the Bay area did not run along the top of the map through Dixon, and Fairfield. It ran south through Stockton, Lathop, and Tracy as that was the easiest path. In fact a bridge at Lathrop, seen almost at the center of the map, is considered the last section of the transcontinental railroad to be completed, as the railroad first went east over the Sierra from Sacramento, and then went west towards the Bay Area.

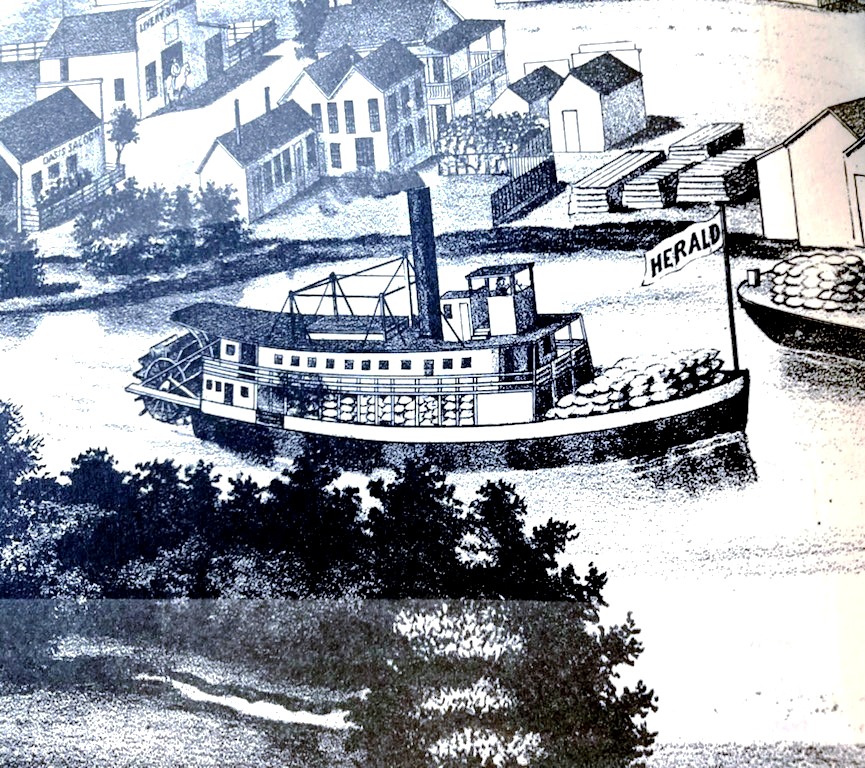

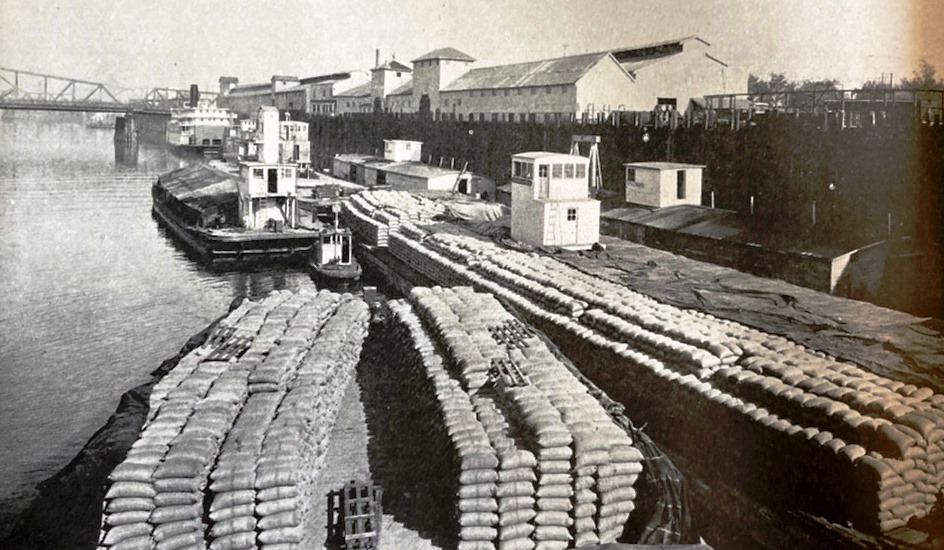

When Sacramento was first settled most of the area anywhere near the river was marsh. Sutter’s fort, almost two miles from the river today, was built right near the edge of that marsh. Where the two large rivers converge, The Sacramento and San Joaquin, west of present-day Stockton, there was a vast amount of marsh. Until the end of the 1800s both rivers where the highways that moved goods and people into the central part of the state. During the winter, the Sacramento would spill way over its banks and could become many miles wide in some areas. During most of the rest of the year there was enough water flowing out of the Sierras that riverboats plied the waters from Kettleman City, about 40 miles south of Fresno, in the southern reaches of the San Joaquin River, all the way to Red Bluff, and occasionally Redding at the northern end of the Sacramento Valley, almost 400 miles north of Kettleman.

The final part of the path south to Kettleman was a trip across Tulare Lake. This was once one of the largest freshwater lakes west of the Great Lakes. Often larger than Lake Tahoe. For many years it had a vibrant fishing industry. For 19 of 29 years between 1850 and 1878 it would overflow into the San Joaquin River. With the damming of the major rivers over the last 150 years that lake is now usually dry. Do not look it up on today's maps as it is gone. At its historical largest extent, in wet years, it covered 690 square miles. Even today, during wet years it will briefly start to form again.

Today, the King River, a major contributor of water to what was the lake, is completely controlled and diverted. The San Joaquin during the summer is a bed of dust over most of its course until you near Stockton, where due to water diversion into it, tidal actions, and the fact that it has been dredged into a deep water ship canal, Stockton is a sea going port, it finally becomes a major waterway again.

Before the water was shunted away for agriculture and also used to preserve fisheries, so much water flowed during much of the year so that not only were boats plying north and south, but many were also able to approach the Sierra foothills in places like Marysville, Modesto, and to the northwest corner of Fresno. In fact, the pipes for the city of Modesto's first public water system were delivered by boat. Today that is a town that seems greatly landlocked. A few even operated up the American River four of five miles to near where Sacramento State is today.

Sacramento sits at the eastern edge of the great Central Valley, and just a few miles east the first geological ripples of the Sierra foothills are visible. Even today during many winters to travel west from Sacramento over land is problematic. Appreciable rainfall, even today, and a three-mile-wide lake forms just west of the city, known as the Yolo bypass, as it is in Yolo County. It shunts excess flood water away from the main channel of the Sacramento river. Until the first bridge was built in 1916 either ferry service or a 50-mile detour south through Stockton and Tracy was required to go around it. During the summer dry months there was use of a seasonal road that traversed it. It was aptly named Summer Road. Today the bridge, or causeway as it is more commonly known, is home to a quarter of a million Mexican free-tail bats in the summer.

A section in southwest Sacramento today, called the pocket because of a large slow bend in the river was historically a swamp as the center of the bend is actually a few feet below river level. A system of levies protects the 30,000 people who live there today, but even in dry months the river level is higher than the neighborhood behind the levy. Some claim that the potential for flooding in Sacramento today is as great as that of New Orleans.

Thus, historically floods in the city and area have occurred periodically. A flood in 1850 submerged the town and wiped out a few nearby small settlements. This happened again in 1861, with flooding lasting 40 days and submerging the town by as much as 30 feet in some areas.

The flooding is bad but sufficient water flow is what made Sacramento prosper. Sacramento sits at the northeast corner of an inverse delta, the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. This conjoining of two large bodies of water covers an area of about 1,100 square miles. The rising sea level after the last glaciation, after having filled the San Francisco bay with water, along with the narrowness or the Carquinez Strait, and tidal action caused sentiment carried down by the rivers to pile up, forming numerous large islands comprised of peat and tule. In its natural state the delta is a large freshwater marsh. Many of these islands have seen extensive agriculture use which has led to soil compactions, along with wind erosion, causing many of these islands to now be below the water level, so many islands are surrounded by dikes. This has caused the area to be called America's Holland. The delta has almost 200 islands, some 57 of which were reclaimed sections of land by building a dike around them and then pumping the water out. The islands are surrounded by 1100 miles of levees bordering 700 miles of water way.

San Francisco bay, delta, and Sacramento river traffic

You can see that Sacramento was in a sweet spot for moving goods and people out of the bay area up towards what was turning into the gold country. Sacramento saw its first boat arrive in November of 1847. When the gold rush started many boats were sailed up to Sacramento where they were promptly abandoned by their crews. Over time a business grew up were builders would scavenge all or pieces of these boats and refurbish or integrate the parts into new vessels.

Early on, the trip from the bay to Sacramento could take a week. By the end of 1849 there was a 70-foot, 25-foot beam side-wheelers that could make 4 knots plying the waters up to Sacramento carrying 40 passengers. Soon larger ships where making the trip in 17 hours. These ships charged a lot for the day for passage and freight. Up to $30 if you wanted a cabin to yourself, or a simple berth, $5. It was reported that some ships were bringing in $60,000 a month on their runs. Incredible amounts of money for that time, worth almost $2 million today.

Most of the early ships used made the perilous journey around Cape Horn to get from the east to west coast. A couple disappeared without a trace attempting the trip. Some were taken apart and shipped in pieces on larger more sea-going ships and re-assembled. Some schooners which originally had masts and sails were converted to river going boats. In the late 1850s local shipbuilding from scratch sprang up.

The routes taken between ports often veered off the main rivers. A favorite route would diverge from the main channel of the Sacramento north of Rio Vista and go up what became known as Steamboat Slough. This parallel waterway provided a much more direct route. Another shortcut for boats traveling between Stockton and Sacramento kept them mostly off the San Joaquin, which Stockton is on, and the Sacramento, which Sacramento is on. This shortcut between the two cities was called the Georgiana Slough after the boat that pioneered the shortcut. This route seems wrought with peril as there is a very sharp bend, fittingly called the Oxbow, and in some places, it is barely 100 feet wide.

Occasionally the boats that were in competition with each other would step that competition up a notch and physically race each other down what could be some very narrow channels. In several cases one would cause the other to ground itself, or via collisions to physically cause damage to the other. One sank after a collision with a snag during a race. On one occasion a wronged captain managed to push a rival, broadside, down the river for a few miles. That aggressive captain ended up having charges brought against him. These confrontations usually happened with passengers on board, and often those customers would get into the heat of the battle and shoot at the other ship or throw projectiles. Often, both ships would be making the same stops and passengers on one would fight with passengers on the other during these brief ports of call.

The start of the gold rush changed Sacramento's course, from the vision of a single man to a community that needed to acquire diverse commerce if it was going to survive. At the beginning all the traffic towards Sacramento, not only the hopeful gold diggers, but also the supplies and merchants looking to make their fortune off those looking to make theirs via gold, would keep the destination relevant. But that would not last, and the town now needed shops, pharmacies, attorneys, and the other trappings of a community. Hunting for gold productively, like about anything, will not progress well, or quickly if the miner must stay a generalist, and fashion everything they need to survive, and not specialize in the hunting of gold for its own sake.

Also, not everyone wanted to prospect for gold, but they saw in the area a need for what they already knew how to do. By 1852 most vestiges of Sutter's New Helvetia had vanished, and a city was going up around a decaying Sutter's Fort.

This was foretold in March of 1848, when a couple of former members of the Mormon Battalion set out from Sutter's Fort to hunt for deer and found gold along the American River in an area that is now flooded by Folsom Lake. This was the second major strike after the discovery at Coloma. Soon about 150 Mormons arrived to search for gold. Many of the Mormons that had fought for the U.S. in the Mexican war had come north from southern California and had gone to work for Sutter. His fort was already becoming a ghost town.

While the gold rush went on Sacramento was working on being other than a supply depot for the prospecting madness in the Sierras to the east. California's first capital was in San Jose, it shortly moved northward to Benicia, before the legislature decided on Sacramento in 1854. Setting up government was a whole new industry for the town. The capital building, which saw construction start in 1860, would take 14 years to complete.

Another endeavor that required manpower and capital was the construction of the Sacramento Valley Railroad, the first incorporated Railroad in California and the first built west of the Mississippi. Originally it was planned that it would run from the river and L Street in Sacramento to Marysville through a roundabout route via Folsom. The route only made it the 23 miles to Folsom.

Theodore Judah was from the east and was brought out to be the Chief Engineer on the project. Later he became the Chief Engineer for the first transcontinental railroad. At the time he came to California there were fewer than 800 civil engineers in the whole country. His and the railroads presence in the area helped ensure that Sacramento would be a railroad center.

In the early 1860s when a colleague from Dutch Flat helped Judah realize that there was a ridge spine that ran east-west between the Bear and the North Folk of the America river that could be used to gradually get to Donner Pass, and then down into Truckee to follow the Truckee river out of the eastern end of the Sierras it cemented Sacramento as the starting point for traversing the Sierras. The path ran from Sacramento through Auburn, Colfax, and Dutch Flat and through Emigrant Gap to the summit. Other paths considered had two summit crossings where this one had only one.

While still a conduit for people and supplies headed for the gold fields by the mid-1850s Sacramento had other endeavors to concentrate on.

Putting the area on the map

The Lead Up to Gold

Before gold was discovered by Marshall, there were five major villages occupied by the natives by the early 1850s within a six-mile radius of Grass Valley. The tribes claimed the Yuba, Bear, and American River watersheds, extending from the Sierra Nevada summit to the Sacramento River.

These villages were very transitory, with the villages being relocated within a decade, and some perpetually being moved, especially on the death of one of the inhabitants. These settlements typically housed an extended family, with grandparents and unmarried relatives included. Six or so conical structures with one or more acorn granaries formed a village, along with a large assembly or dance house in the major villages. They selected open, flat ground on ridgetops, or gentle slopes or benches with southerly exposure.

The hill Nisenan territory experienced intermittent intrusions by non-native people prior to the gold rush. Spanish, as well as Russian, exploration parties from the settlements along the coast had explored the interior is early as 1808. In 1821, the same year Mexico's independence from Spain occurred a Spanish expedition, somewhat detached from the events to the south, reportedly reached the Valley Nisenan territory at the confluence of the Feather and the Sacramento rivers. Armed with a canon, the Spanish expedition of 75 men and 235 animals visited a string of settlements west of the Sacramento River. Interactions varied, with some turning violent. One particularly destructive battle resulted in the death and injury of several Native Americans.

In 1827 Jedediah Smith traversed the central valley and foothills. His route crossed Nisenan territory. His descriptions of his travels opened the door to French and English-speaking fur trappers entering the valley from the north and east, ushering in an exploration and settlement period by people of European decent. In 1832 and 1833 a trapping party typical of the era came down from Fort Vancouver into the region. This 100-person party engaged in trapping for extended periods on the lower Feather and Yuba Rivers, just north of Grass Valley. Their camps could be likened to a nomadic pluralistic village, with men, women, and children of diverse backgrounds. A journal by the leader of the party included numerous entries about giving food and trifles to the local people, probably beads, and trading them for food such as salmon. Although interactions were generally peaceful, the trappers responded aggressively when traps or horses went missing. Foreign disease entered the valley with these trapping parties. An estimated 75 percent of the indigenous population died from epidemic disease by 1833.

Also, around this time, the Franciscan missions were undergoing a process of secularization, sparking an increase in land grants. Mexican authorities allowed foreign settlements to populate the frontier. Rancho expansion reached into the interior beginning with John Sutter in 1839, and more non-Hispanic immigration and settlement soon follow during the 1840s. Numerous trails were beaten across the Sierra Nevada.

Expansion into California exploded in 1849 after President Polk announced the finding of gold in his State of the Union Address on December 5th, 1848. "The explorations already made warrant the belief that the supply is very large, and that gold is found at various places in an extensive district of country," he declared. Up until then many thought the discovery was a hoax. He optimistically pronounced that economic opportunity in California would allow the US to compete with Great Britain, the dominant global power at the time. This unleashed the largest migration in United States history and drew people from a dozen countries to America's fringe.

Polk, who was president from 1845 to 1849, a democrat, was the president most closely associated with the "Manifest Destiny." Under his tenure Texas and California were added to the country, and now he saw a way to promote increased settlement in the newly acquired territory. The discovery of gold in California also made it possible to put the U.S. monetary system on the gold standard in the 1870s because gold became more plentiful.

Up until Polk's announcement only approximately 500 people had migrated west overland that year, and some 6,000 total Argonauts arrived the next year, 1849.

Gold was first discovered in 1842 by a native Californian northwest of Los Angeles. It was mined by miners from Sonora, Mexico, until 1846 when Californios started agitating for independence from Mexico. The Bear Flag revolt caused many Mexicans to leave California.

Native Americans had known that there was gold in abundance in the Sierras. They had their own system of currency and trade, and they looked upon gold as nothing more than a shiny material, of no intrinsic value. It is claimed that the term "five clams" used to denote five dollars came from the fact that some tribes used clam shells as currency. The color of the shells, their vibrancy, delineated a shells value. What also increased their value was when they were strung together as decorative jewelry. The island of Manhattan, today the financial center of the world, was purchased from Native Americans with shells.

The problem for the Native Americans was that European settlers, with metal tools, could much more efficiently create elaborate "Wampum" as some tribes referred to their trading currency, thus "inflating" the currency supply and lowering its value. Many tribes were forced to only trade in hard goods because of this. Some Natives in the area soon learned that they could trade with settlers by using gold. Also, some, again for hard goods, would lead early prospectors to places where they knew gold was abundant.

This led to devastation for the Native Americans, for the inrush of prospectors brought more unfamiliar diseases, plus an often-hostile attitude from the newcomers. The horrific result was the loss of approximately 240,000 of them over the next few decades.

In short order anywhere there was running water coming out of the Sierra, you found groups that were placer mining. Placer mining is sifting through alluvial deposits. Alluvial is unconsolidated soil or sediment, that has been eroded, and reshaped by flowing water, and redeposited in a stream bed. Often when a creek or river changes its course, which over time always happens, the deposits might no longer be in a running stream.

The gold discovery brought hundreds of thousands of people to the state in a few years. The initial settlers were from nearby, Oregon, Latin America, or Hawaii, known as the Sandwich Islands at the time. By 1855 300,000 forty-niners had arrived, about half by boat, and half overland, many hoping to find their fortune in gold, many to provide services, and others to prey off the miners. Soon settlements were springing up all along creeks flowing out of the high Sierras. Many were ephemeral, camps that were transitory and soon gone. Others gathered enough of a foothold to become permanent, and still exist to this day. Towns like Sonora, Angel's Camp, Jackson, Placerville, Auburn, and of course, Grass Valley and Nevada City.

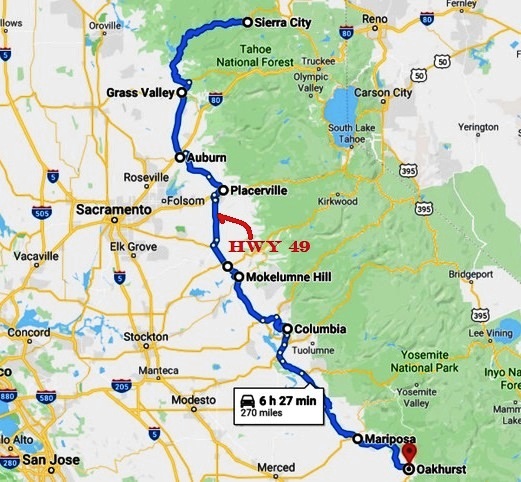

Today there is a highway that follows the Mother Lode, Highway 49, aptly named after the 49ers, the immigrants that lead the invasion that started in force in 1849. The mother lode is the name given to the principal vein of gold in the area. This vein exists because of the Melones Fault. This fault runs about 250 miles from Downieville in the north, about 47 miles via highway 49 northeast of Grass Valley, all the way south to Mariposa, southwest of Yosemite.

The present-day highway follows the mother lode, only straying away for short distances. Long before it was a fault zone it was a submerged ocean canyon. Fluids generated in the deep parts of this zone left deposits of gold. Later when the zone became a fault line, the shattered and broken rocks, slate, granite, marble, and quartz, depending on where you are along the fault, allowed access to the gold within the vein. Most of the gold mines were within that narrow vein, and the highway now literally runs over many of the mines. In fact, the highway and an adjacent Safeway grocery store sit atop one of the entrances, called a head frame, to what was one of the largest, deepest, longest, and richest gold mines ever, the Empire Mine in Grass Valley.

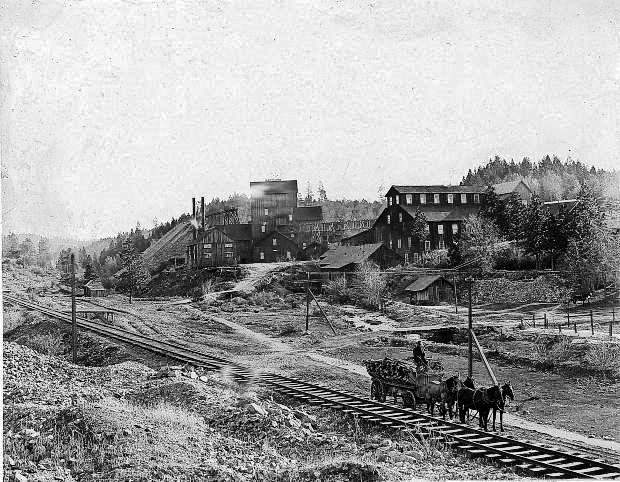

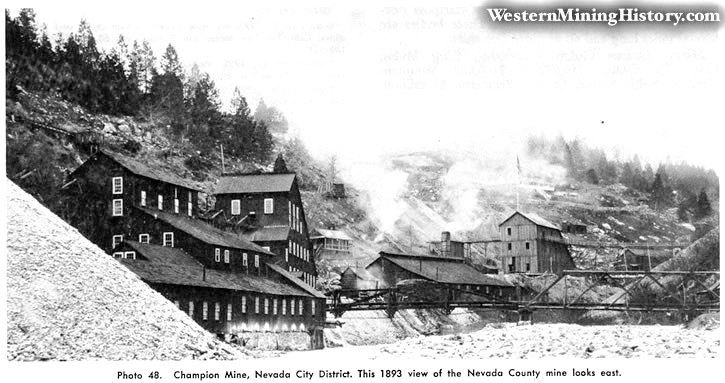

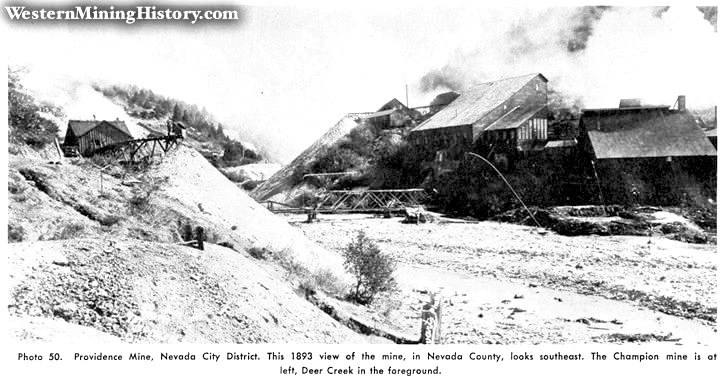

Two vastly different towns

Late 1800s Nevada City

View to the west from the courthouse in Nevada City

To support the mining efforts in the area, two distinct towns grew up. Their economies, society, and politics were often based on remarkably different outlooks. Over time they sometimes swapped worldviews and philosophies. At times, the towns were even suspicious of each other.

The two town's centers are about five miles apart, situated at roughly 2,500 feet (760 m) elevation in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountain range. By car they are approximately 57 miles from the state capitol in Sacramento, and 64 miles from the Sacramento International Airport. If you are leaving the area by plane that is your likely destination. Often Reno seems to have deals on flights and so some make the 88 miles trip east to Reno. The towns are about 140 miles northeast of the San Francisco Bay area, which over time had a major effect on these two towns, as we will see. Grass Valley's population is around 13,000, while Nevada City is around 3,000.

The most popular story about Grass Valley’s founding is that a group of settlers who came west through Truckee and camped near the junction of Steep Hollow and the Bear River, a few miles southeast of the present day towns. Their cattle wandered off and were found grazing on the lush grass in a meadow that they named Grass Valley. Grass Valley, which was originally known as Boston Ravine, was later officially named Centerville. This is just southwest of where highways 49 and 20 come together today. When a post office was established in 1851, it was renamed Grass Valley for unknown reasons. In the early 1850s Grass Valley was considered the more exciting of the two towns. That distinction moved to Nevada City in the mid-50s. Nevada City incorporated in 1860.

Boston Ravine, after a company of the same name, founded by settlers from Boston, erected a four-cabin settlement there in the fall of 1849 and started mining along Wolf Creek. Various forms of Placer mining were conducted there for a decade before the era of Quartz mining. That first winter was brutal on the 20 men inhabiting the site with record snow fall. The area being at 2,400 feet in elevation can see snow, especially when cold air coming out of the Gulf of Alaska, pushes its way up and over the Sierras.

The 20 miners who camped out in Grass Valley emerged through the winter and early 1850 to a fresh wave of would be placer miners. About 15 cabins, the first store, a hotel, and family were in town by the end of the summer. A transportation network quickly developed to service the gold mining communities, with the Nevada City Road branching off the Donner trail by 1850. Grass Valley and Nevada City served as the trading centers at this time, catering to the young single miners. The town was also populated by small merchants almost indistinguishable in age and attitude from their customers. As many gold seekers settled and develop families during this period, the population of California continue to grow from 225,000 in 1852 to 380,000 by 1860.

Extracting the Gold

When the rush originally started the miners largely ignored existing property rights, especially those claimed by Sutter, and they rushed to the rivers, in spots where the gold was so richly concentrated that simple placer mining could be employed. Since the gold is heavier than most other materials it tends to settle out first in areas of slower moving water. So the first minors simply panned for gold, where they would scoop up some alluvial deposits and slowly agitate and flush the pan with more water counting on the heavier gold to settle to the bottom of the pan with everything else slowly being flushed out. This was a largely inefficient process as it could take about 10 hours to process approximately one cubic yard of material. Early on when panning was in its infancy, that was not a bad proposition as there was plenty of easy gold for the picking, as they say.

Placer Mining

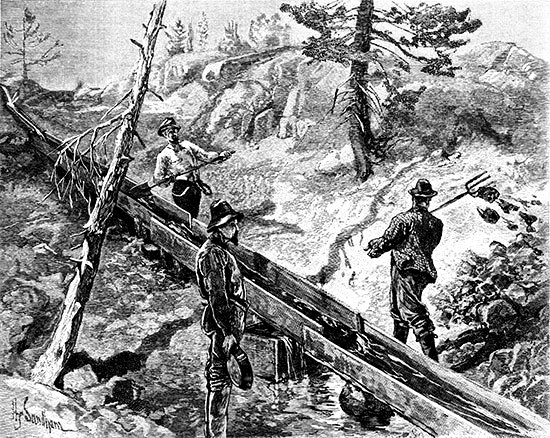

Soon more efficient methods were adopted. A rocker box or cradle was used to process more material at a time. It consisted of a box that could be rocked that had several screens, riffles, and channels along the bottom of a tray to separate the heavier gold from the rest of the material that was slowly flushed out. It allowed the miner to process three or four times as much material at a time as a simple pan would.

Rocker box or cradle

Next up the scale would be a Sluice box, this allows shovelfuls of material at a time to be dropped into the top of it with a source of water running through it. Again, sets of riffles along the bottom of the box would trap the gold. While this can process lots of material it is claimed that they only recovered 40% of the gold shoveled into it. So, the tradeoff was more material could be sifted through at a time, at the expense of gold that went unrecovered. But volume of soil processed won out.

By 1850 most of the easily accessible gold had been collected. Now gold miners got more aggressive about hoarding the sites that still might harbor easy to harvest gold. There were some organized attacks on foreign miners, especially Latin Americans and Chinese. The newly founded California Legislature in 1850 passed a foreign miner’s tax of $20/mo. That would be over $600/mo today.

Besides the diseases the outsiders brought, the miners forcibly started evicting Native Americans from their lands. Some responded by attacking the miners. This led to attacks against native villages. Being outgunned led to massacres of the natives. Those surviving often starved without access to their food gathering areas.

This led to a temporary military post being erected southwest of Grass Valley, near present day Marysville. For three years Camp Far West as it was known, was strategically placed to safeguard the travel routes to the area's mines. The post's commander Captain Hannibal Day, noted that the hardy and well-armed miner was being defended by an under-fed and scurvy-weakened soldier from "a miserable race of savages . . . armed only with the bow and arrow." That said much about the plight of the natives and their treatment.

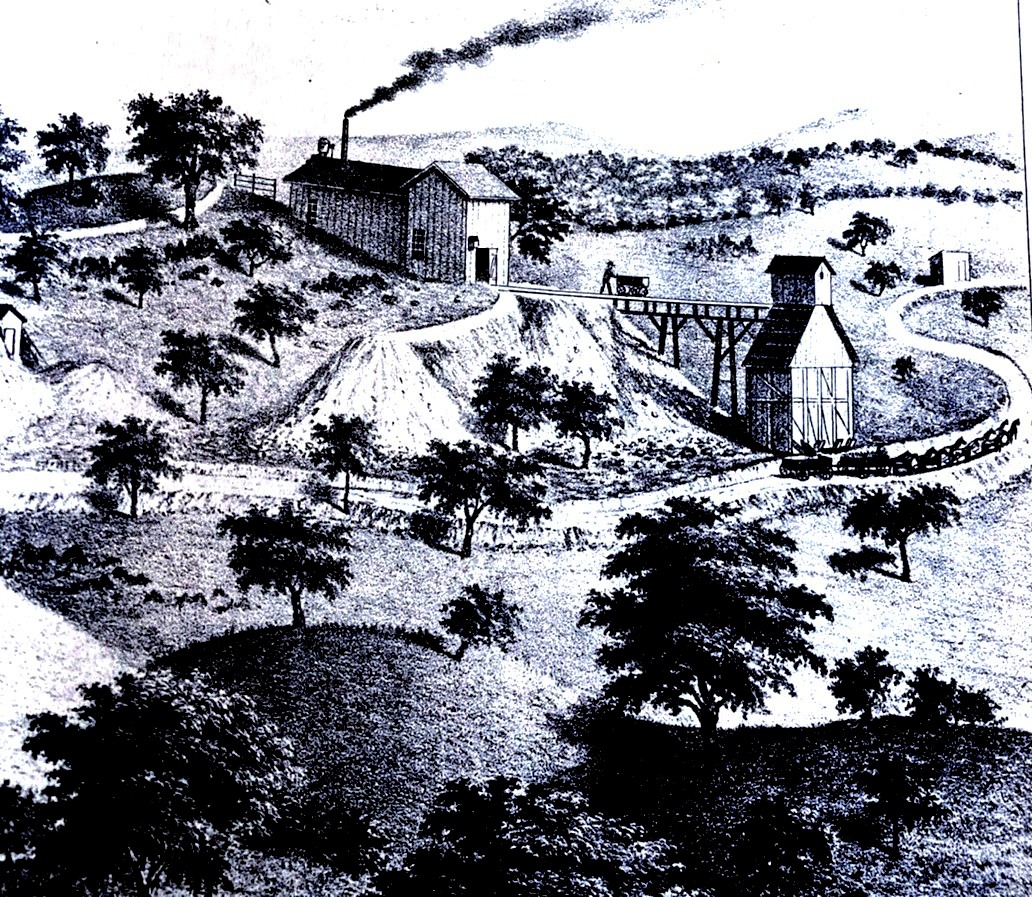

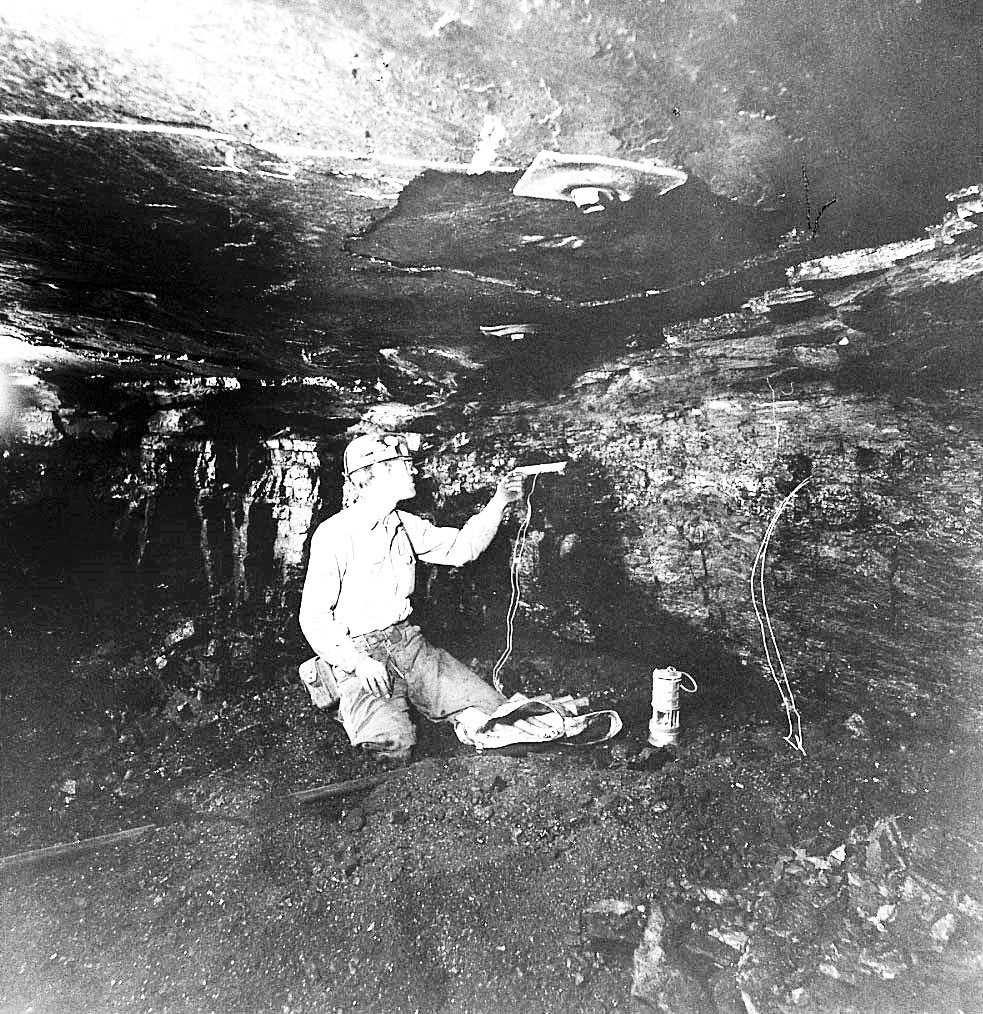

Deep Shaft Mining

Soon to extract serious amounts of gold, mining had to go underground. Miners started engaging in "coyoteing." Digging a shaft 20 to 40 feet deep into deposits near a stream, and then tunneling out from the shaft. Gold mining continued to get more sophisticated and destructive. Miners at times would divert a creek away from its current streambed and into a sluice beside it. They would then dig out the exposed streambed.

Coyote Hole

Hydraulic Mining

By 1853 and new level of intrusion to extract gold was in use. Hydraulic mining, employing jets of high-pressure water were used on gravel beds that flanked the river, but also on entire hillsides and bluffs. The loosened gravel would then pass over sluices. This resulted in large amounts of gravel, silt, and other materials to be washed downstream. The major economic advantage to this method was overhead. Hydraulic mining took one quarter of the manpower that other types of mining took for the same amount of gold extracted.

High Pressure mining: The loosened gravel would then pass over sluices (red)

Where this type of mining was done still bears the scars today, as the topsoil has been washed away and the underlying rock does not support vegetation. One of the worse examples of this type of mining is only a few air miles north of Grass Valley on the other side of the South Yuba river canyon on a ridge separating the Middle and South Forks of the Yuba River. This area became known as the Malakoff Diggins. In 1866 the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company was formed to mine this area. By 1874 they had carved a 7,800 ft long drainage tunnel through a ridge to facilitate the processing of 50,000 tons per day of gravel set loose by seven giant "monitors," giant water cannons, working 24/7. To allow the round the clock operations, an early use of high intensity electric light was installed. The waste tailings, also called slickens, were dumped into the Yuba River, which eventually destroyed farmland as far down stream as Sacramento.

Much of those tailings can be found downstream where they choked rivers and stream beds. Some areas downstream saw those beds raise approximately 100 feet. The I street bridge in Sacramento had to be raised 20 feet. Eventually this situation led to one of the first environmental court decisions. The Sawyer Decision, named after the judge who handed down the ruling, caused this type of mining to cease in 1884.

One result of this type of mining was the invention and implementation of river dredging to clear out debris in the waterways all the way down to the San Francisco Bay. This dredging was also applied to the Yuba River near Marysville. But by 1904 onward most of the dredging was done away from the river in what came to be known as Yuba or Hammonton Dredge Field, named after the man who started in the area with two dredges.

Dredging

The dredges appear much like industrial versions of a flat bottom riverboat with a bucket line conveyor in the front that would scoop up material and convey it into the boat where it usually was dumped into a circular rotating screen sloped downward. As the material traversed down this screened tunnel it first encountered a small mesh screen to allow the fine material, including gold to filter out. As the material continued down the tunnel it encountered larger mesh screen to let the large chunks or rocks fall out. The fine material fell into a sluice box, which worked as other smaller ones used alongside streams. All the material that was discarded, the tailings, were expelled out the back by a spreader or stacker as it was called and was left behind the boat as tailing piles.

The boat would reside in its own man made pond, digging its way forward and filling in the leftovers behind it. The pond literally only surrounds the boat and moved forward as the boat dug its way forward. Much gold was left behind, and in some instances, the same ground was literally plowed through again. But by the late 1960s the extraction of gold became uneconomical and the search for gold stopped. But recent satellite photos still show a couple vessels sitting in these artificial ponds, supposedly now digging out aggregate to produce concrete. This area from the air is said to resemble a vast network of intestines. The field is about four miles long and extends a little over a mile south of the river and is about 15 miles downstream from Grass Valley.

This was not the only area nearby that underwent the dredging process. About 50 miles south of Grass Valley, on the edge of the eastern Sacramento Valley was the Folsom Gold Field. This was along the American River, most of it south of it. It stretched 10 miles downstream to the Sacramento suburb of Fair Oaks, and south from the river by six miles. It had dredging operations into the early 1960s. The Aerojet rocket engine company settled in the area, as they found the tailing piles made good abutments to retain rocket blasts during testing.

While none of the others were anywhere near as massive and invasive as the Yuba and Folsom fields, many rivers flowing out of the central Sierras had dredging efforts where those rivers met the valley to capture gold that was being wash out of the mountains downstream, by natural forces, or the gold set loose during Placer mining but not actually recovered in the mining process. It is estimated that most of the gold dug up was lost downstream.

Bringing Order

To take gold mining from a "rough and ready" endeavor and turn it into a semi-respectable pursuit would take some organization. There was a town just west of Grass Valley with that name. It was named after the company that started a mining camp there in 1849. The company took its name in honor of the newly elected 12th President of the U.S., Zachary Taylor, known as "Rough and Ready." Taylor lasted only a year in office before he died of what was most likely a food born illness. During his short tenure he faced tumultuous times leading up to the Compromise of 1850.The man who helped shape the mining legal landscape to bring some semblance of order was a Yale student who came west in 1850 to find his fortune and found some success trying his hand at gold mining before becoming serious about completing his law studies. His name was William Stewart. He started mining along the Yuba River not too far upstream from where the Malakoff Diggins were later set up. After some success he decided that mining was not a good long-term career and studied to pass the bar exam, which he did in 1852. That same year he was chosen as the District Attorney of Nevada County. A few weeks later he was selected to chair a County Miner’s Committee to iron out mining claims and to mitigate the many disputes that were continually cropping up in the area. This committee hammered out uniform mining laws for the area that was soon adopted by others.

Up until that time, in the absence of federal or state government, or any other social order, local mining districts began to form when the population of the miners reached a level requiring some structure needed to avoid conflict. Throughout California companies of placer miner's setup mining districts with codes of governance predicated on the ideals of individual rights, public property, and favoring first come, first use. The sheer numbers of minors by 1849 led US Army Colonel Richard Mason to permit all to work freely, though he would have preferred to levy some sort of fee based system benefiting the federal government but knew he could not, due to being so outnumbered. Stewarts committee set out to codify the conventions and business ethics among the mines and miners involved.

They laid the groundwork for what eventually became three principles for governing mining:

1) that mineral land in the public domain should be open to exploration and occupation.

2) claims established under local customs developed by each money district shall be recognized.

3) the title to land with certain minerals may be obtained.

Because of his leadership in crafting this initial legal groundwork and his understanding of the subtleties of what they laid forth he became one of the best known and wealthiest mining lawyers in the west. The groundwork that Stewart’s committee put forth eventually became laws that congress passed in 1866, and 1870, and then consolidated into the General Mining Act. Provisions of this act are still in effect today.

In 1854 he became California's Attorney General. In 1860 he left the state for Virginia City in the Nevada territory where he became a leader in getting the territory to statehood. When Nevada was admitted in 1864, he was selected as a Republican to the U.S. Senate. Stewart is credited with authoring the Fifteenth Amendment in 1868, which was ratified in 1870, giving voting rights to all men, regardless of race, although some restriction against Native Americans and the Chinese continued to 1924, and 1943 respectively. While not without controversy, it was later claimed that he was a servant to railroads and mining interests, but his work did lay the groundwork for how mining activity in the area would be conducted for the next 90 years.

Even while mining was becoming an industry where the sole prospector was increasingly finding it difficult to survive, a minor nationwide economic depression from 1856 until 1860 encouraged many to continue small scale placer mining, even though the work was becoming far more complicated than simple panning. Increases in gold mining consistently occur during slow economic cycles. The Civil War interrupted that, as extracted gold fell dramatically. By the end of the war it had continued its precipitous drop, down to half what it was when the war started. The decline resulted as much from the depleted placers as it was from miners leaving the gold fields to join the conflict. In 1850 miners consisted of 75% of the male workforce. By 1860 it was down to 38%. The individual, or small groups of individuals working a claim was rapidly diminishing.

The declining numbers of miners in the state's population illustrates the draw to other strikes in other states and territories, other occupations, or simply giving up and returning home. In Grass Valley, however, the influence of gold mining in the community was moving in the other direction, from 71% of the population engaged in mining in 1850 to 76% of the population in 1860. The town was becoming a hard rock mining town as it was discovered that below ground lay quartz veins laden with gold, while Nevada City was turning towards commerce and hydraulic mining. Increasing its reliance on mining, Grass Valley turned towards quartz mining. Between the two towns, because of this early path divergence, initially at least, the town of Nevada City was more elaborate and sophisticated than Grass Valley.

Until a Federal Mint opened in San Francisco in 1854, prospectors relied on any of the more than 20 private area mints that refined and stamped their own coins. It was also common practice during this era for specie, or pinches of gold dust, to be used in local transactions. Many of the miners preferred to send some of their wealth home, and for this they turned to gold dealers who purchased gold at a lower price off the miners and marked it up and sold it to banks back east.

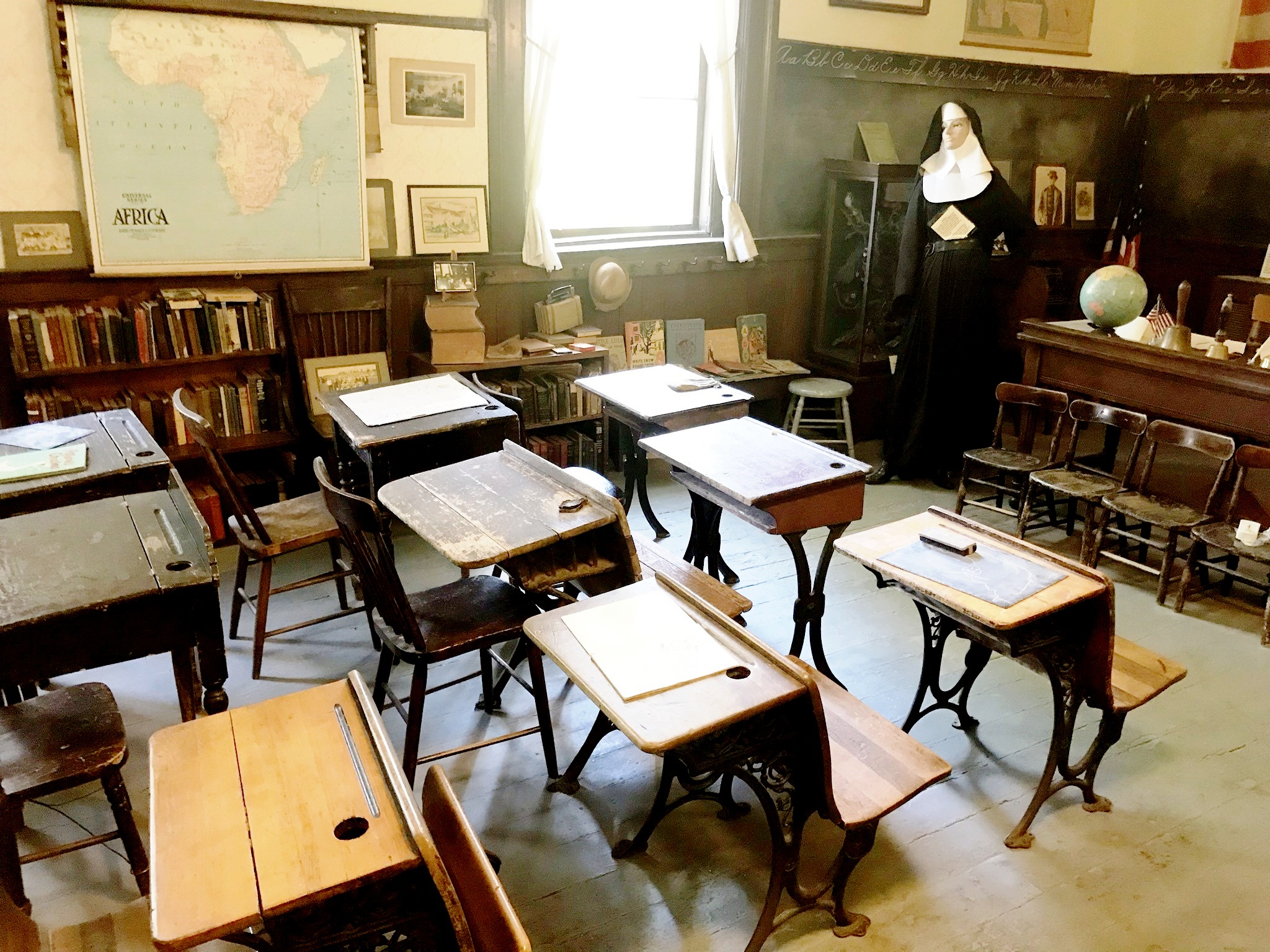

Because deeper and more elaborate mines were starting to be sunk in the Grass Valley area after gold bearing quartz was discovered in the area in 1850, many of those who came to settle in Grass Valley were tin miners from Cornwall, England. They were attracted to the California gold fields because the same skills needed for deep tin mining were needed for hardrock or deep gold mining. Tin mining was an industry that was in rapid decline in England. Many from Cornwall specialized in pumping the water out of very deep mining shafts which continually accumulated. This migration to the new world followed the disastrous fall in tin prices as large alluvial deposits began to be exploited elsewhere in the world.

There are five distinct eras of gold mining that defined the dominant patterns across the first 8 decades of Gold mining in the Sierra Nevada. This period lasted from 1849 to the start of the Great Depression at the end of the 1920s.

I) The first era was the original gold rush from 1848-1850. The news of abundant gold spread across the globe in a well-documented order: beginning locally in California; then to shipping ports across the Pacific; from Oregon to the Sandwich or Hawaiian Islands and throughout Central and South America. Migrations of people from each place headed in turn to the poorly known, often uncharted mountains of California. James Marshall, who is credited with discovering gold at Sutter's Mill, is also given credit for being the first to pan along Deer Creek in the Nevada City area in 1848. By October 1848, a group from the Willamette Valley in Oregon took a large amount of gold from Wolf Creek. They soon left, being unprepared to deal with the coming winter. The surface placers lasted until about 1855, after which river mining accounted for much of the state’s production until the early 1860s. An early record for gold production in California occurred in 1852, weighing in at over 3.9 million fine ounces, this whole period, however, is characterized by annual production nearly as large. Beginning in the 1850s and continuing after all the stream placers had been depleted, miners increasingly worked for wages, as there were fewer opportunities to work independently, or to join in small joint stock companies. Wages also decreased, from exorbitant highs above $10 a day during the gold rush, to 2 or 3 dollars or less a day by 1860.

II) The second occurred due to the Civil War. A significant slump in California mineral industry came in the wake of the Civil War, between 1864 and 1872. By 1864 the gold rush was over, attributable to the exhaustion of stream and bench placers easily processed with a little experience or investment. By 1867 most of the major mines in the area had been located, and there were 30 stamp mills operating to support them processing extracted gold and 1,600 men working in the industry in the Grass Valley area alone. With the transcontinental railroad completed in 1869, some Chinese workers headed to the mines, where they found jobs or purchased claims originally located by euro Americans. Many Chinese who worked on the railroads also became laborers for large, capitalized gold mines, were they were considered less quarrelsome than many turbulent and riotous Euro-Americans. Discrimination however, made finding gainful employment difficult. In hydraulic mines, for example, Chinese were employed in the least important work, in drudgery that would be difficult to get competent white labor to perform. They did work some placer claims in the Grass Valley area during this period. But the Chinese were barred from working inside the gold mines. So the local Chinese community turned to farming and domestic labor, keeping orchards and gardens, and some operated a laundry along Wolf Creek.

III) A worldwide economic depression of 1873-1877 sparked another mining boom. During economic downturns, the stable value of gold increases in relation to other stagnating prices, drawing the attention of investors and the unemployed. Gold mining regained importance across California between 1873 and 1892. Gold production climbed to a peak of nearly 1,760,000 ounces in 1883 (still significantly lower than the 1852 record). Even this lower amount had not been seen since 1862. All of Europe adopted strict gold standards during this period. Congress suspended silver coins in 1873, effectively adopting a gold standard as well, and passed the Specie Payment Resumption act in 1875. In part, the act of 1875 was intended to restore confidence in the federal monetary system, which had introduced greenbacks during the Civil War but failed to pin them to a gold standard. This act corrected that. While there was a steady return to gold mining, the number of miners in the state did not regain their former dominance. This was due in part to new technologies that required fewer workers, particularly in large hydraulic operations until they were banned in the 1884 Sawyer decision. Overall California gold mining declined after the Sawyer decision, but it had little effect as the mining stayed the dominant industry in the area. By the mid-1880s Grass Valley quartz mines were the primary mining in the area, and they needed experienced expert "hard rock" men. As we will see shortly several large deep mines are what dominated the business from then on.